|

DILI, February 2001.

EMPLOYMENT IS A CRITICAL issue in East Timor. Looking around Dili and the districts, it's obvious there aren't many people with waged jobs. Many of the jobs there are are with the government or government supported services like the hospitals.

A recruitment officer, responsible for filling Timorese job vacancies in the government, UNTAET, told me that just about all the qualified Timorese now have jobs. Most of those who are left are under skilled. She says she has people with four years of primary school education insisting on applying for jobs that require university degrees. It shows how desparate people are for work, and how little opportunity they have to skill themselves for it.

So if people don't have jobs, how do they make their living in a place

where there is no social welfare system? Many families have staked-out a

small square of land and set up a stall to sell things from. There are

thousands of these self-employed families in Dili. Other people don't even

bother with the shop and just walk around carrying their speciality, like

avocados or strips of meat or cigarettes or water or mothballs (truly). I

guess you'd call it subsistence retailing. It seems to be working for

some, or at least plenty are doing it.

So if people don't have jobs, how do they make their living in a place

where there is no social welfare system? Many families have staked-out a

small square of land and set up a stall to sell things from. There are

thousands of these self-employed families in Dili. Other people don't even

bother with the shop and just walk around carrying their speciality, like

avocados or strips of meat or cigarettes or water or mothballs (truly). I

guess you'd call it subsistence retailing. It seems to be working for

some, or at least plenty are doing it.

There are two other common forms of self-employment or contracting. One is the entry level job that is popular with new urban arrivals all around the world: taxi driving. And the other is money changing. Black market money changing is an all hours service provided very honestly by hundreds of Timorese young men around Dili. With Indonesian rupiah, Australian dollars and US dollars all circulating here, people often need to change money. These people provide an essential and convenient, albeit black market, service and at the same time give you a better rate than the bank.

What private sector paid jobs there are, are mostly in service. They could be summed up as security, retail, hotel and restaurant staff. There is also a construction industry that is pretty much run by malaes (foreigners) but staffed by Timorese.

Those business people who publicly look for workers are invariably inundated with applicants. The Employment Services here says that sometimes a thousand people apply for the same job. Do you get the sense of the desparateness they have?

In this rather uncertain time in East Timor, when many businesses are just finding their feet, there are also increasing numbers of labour relations disputes. If businesses can't or don't honour their employees' contracts, workers here are well aware of their rights and are willing to take their boss to arbitration.

Currently, these cases are being resolved with the help of Jim Robertson, a Scotsman contracted to the UN. Robertson's actual job is Vocational Training and Education Advisor. He says he is doing labour conciliation because no one else is doing it. I suspect that he and his colleagues know that if no one was providing a place for arbitration on labour issues, people would take matters into their own hands. If that sounds threatening, it is.

Robertson says there are a couple of problems with this arrangement. One is that, while most cases are resolved, a few have not reached agreement and, at this point and in the foreseeable future, there is no "higher authority" to take the disputes to. Nobody knows what to do next. The other problem is that he is being distracted from the job he was hired to do which is to develop vocational training and education policy and strategies. So at the moment, there are none.

Statistics on employment have only just begun to be recorded. They won't even know how many people there are in East Timor until people enrol to vote in the elections late in 2001. So as you might expect, there is no accurate way to estimate the unemployment rate is. But government briefing papers refer to it as "high".

The nation's first, and as I write this, only Employment Services office was opened in August, 2000, in Dili. It has a Timorese manager and six staff. Their brief is to register job seekers and job vacancies.

During their first month, September, last year, they registered about 1,000 job seekers and placed about 100. In January this year they registered 870 job seekers and placed three. In the first ten days of February, they registered 1,254 job seekers but there were no placement figures in the document I saw. I'd say, realistically what they are doing now is registering job seekers but not sourcing jobs.

Staff describe mornings at the office as chaotic and I got the impression it can get frightening. More and more people are coming to the Employment Services in desparate need of a job.

Jim Robertson was one of three international UN staff I spoke to at the Division of Labour and Social Services. Another was Japanese national Kay Abe-Nagata who had been in East Timor two weeks. Her brief is the politically attractive development of employment strategies for war disabled people. Abe-Nagata said she had spent most of her first two weeks trying to get a grip on the convoluted government structure. I doubt that many people even try and I question whether anyone truly understands it.

Femi Aguda, a Nigerian who is a UN Volunteer, specialises in small and medium sized business skills training. He has organised two " training of trainers " courses since he arrived in August, 2000 by bringing in a consultant from Sydney as the trainer. The course material was developed by the International Labour Orgainsation and is two weeks long, with a week break in the middle. Aguda's programme was directed towards NGOs but he says that very few NGOs are focused on enterprise and I get the impression he has not found the people who would benefit from this type of training.

I met a Timorese man who took the ILO course. He told me that except for the bookkeeping part, he didn't find the course much use. He said there was no attempt to make it relevent to Timorese people and that it was based on American and British examples. The fact that the course was supposedly designed for developing countries and has been used elsewhere, does not necessarily mean it is effective. All that means is that some consultant fulfilled a contract by writing it and bureaucrat is ticking a box that says UNTAET is fulfilling an obligation by running it.

Aguda and Robertson both told me, with exasperation, that there is no employment policy. They say they are operating in a vacuum. In fact they are operating out of a large portable Kobehut along with most of the rest of the Department of Social Affairs.

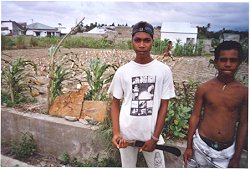

While my experience has been in the urban setting of Dili where unemployment, and youth unemployment is particularly apparent, East Timor is traditionally an agricultural economy. And, while many people want real opportunities and 'modern' futures for themselves and their children, you can't discount subsistence fishing and farming as important means of livelihood. There is no doubt that throwing a net over the reef from a dugout outrigger canoe just 80 meters from shore is important work. Just as tilling a plot of corn, cucumbers, beans and tomatoes and tending a coconut palm, a banana tree, a few papayas, are significant and respectable elements in the matrix of work in East Timor.

However, people want to regain the standard of living they had while the Indonesians were here. In the towns, they are only going to get this when they get decent paying jobs.