|

DILI, January 2001.

I RECKON THE PEOPLE of Dili have an affinity for smoke. There are always fires. If there isn't a rubbish fire going at one house, there's one two doors down whose smoke wanders through the whole neighbourhood. Bike past a cornfield and there wil be somebody raking green leaves onto a smouldering heap and the smoke drifting across the road and seeping through the banana plantation. The carpentry workshop at Futo is a totally open walled, pole structure with an iron roof but it's often awash in smoke. If it's not the cooking fire from next door or a Futo man burning off wood shavings, it'll be one or more of the carpenters who has bought or begged a Gudang Garam clove cigarette. The other day I was standing with my back to the sea looking at the hills behind Dili only two km's away. The haze reminded me of LA.

One reason for much of this smoke is there is no rubbish collection.

Imagine New Plymouth with no rubbish collection. Then imagine a city the

size of Hamilton with no rubbish collection! The only thing to

do with rubbish is to sweep it into a heap, leave it long enough for the

pigs, chickens, goats and dogs to go through it and then torch it. I've

become a litterer. What am I supposed to do when I finish a 1.5l bottle of

water, of which I buy two each day? I leave it where I finish it. There's

no right place for it. If I take it home, Joanna is just going to burn it

outside my window. Most Timorese know that plastic water bottles make good fire starters. Now: big inhale.

One reason for much of this smoke is there is no rubbish collection.

Imagine New Plymouth with no rubbish collection. Then imagine a city the

size of Hamilton with no rubbish collection! The only thing to

do with rubbish is to sweep it into a heap, leave it long enough for the

pigs, chickens, goats and dogs to go through it and then torch it. I've

become a litterer. What am I supposed to do when I finish a 1.5l bottle of

water, of which I buy two each day? I leave it where I finish it. There's

no right place for it. If I take it home, Joanna is just going to burn it

outside my window. Most Timorese know that plastic water bottles make good fire starters. Now: big inhale.

I am living in a different family home now where there are three other malaes, who are Australians. The term malae is from the first foreigners who came to Timor from Malaya. It is used similarly to pakeha, but has an added respectfulness about it that must be a holdover from colonial days. Often when I'm biking along, children start shrieking "malae! malae! malae!" waving frantically and looking so pleased when I wave back or touch their hand, if they're close enough. And it's not just the children who call out. There is some kind of buzz an East Timorese gets by getting a malae's attention. And there is something somehow flattering about the fact that they want it.

The father of my new family, Alvaro (roll that 'r') was a public relations person for the Indonesian administration during the occupation. He says he had a good income, books, a satellite dish and tv, car, motorbike and power 24 hrs/day: a right middle class life. These things changed since the referendum.

The other night Alvaro told me about their experience after the people voted 78% for independence from Indonesia and the military began emptying and ransacking Dili. There were no questions being asked. Alvaro's two oldest boys, Aberi and Alex, in their early 20's, went into the hills. Alvaro, wife Joanna, 15 year old Jacinta and the three young boys, Joel, Bobby and Iku all stayed in the house, waiting.

He said the military came through the neighbourhood with guns and forced them onto a truck and they were taken away with what they could carry. Having been on some of the roads here, and knowing that every town they would have passed through would have been a smouldering ruin or even still burning, I can imagine a terrifying journey. They were not told where they were going and for all they knew they could have been being taken away to be killed. At one point the truck was sitting idling and the door was pulled open by a boy about 12yrs with drugged, bloodshot eyes and holding a rifle. I can only begin to imagine the deathly dread that must have gripped the people in that truck, and the relief when the door closed again.

They were taken to a refugee camp near Kupang, West Timor, over 500kms away. Alvaro scowls when he says he didn't like living in the camp. After a month, he says he arranged for the family's return to Dili on a refugee flight. However, there was last minute hitch and there was only room for him and so he went alone. Four days later, to his immense relief, Joanna and the children followed. The older boys had already returned.

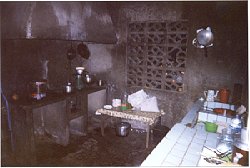

The house had been stripped. It had been fired as well but some of the ceiling and roof timber was intact. In fact, this house fared well compared to others in the neighbourhood. Some are now concrete shells, some merely foundations. Those that didn't have concrete floors now have corn planted in them. If you can't live in your house, I guess you can garden it.

Different lodgers have helped redevelop the place with beds, plywood

ceilings and paint. Now there are lights and power outlets in each room

and good netting on the windows of the bedrooms so I'm no longer sleeping

under a mosquito net. We all use the Asian toilet and mandi type bathing.

I bought a fan which will stay when I leave. I have a table and

chair and a large cardboard box with a piece of plywood on top for my

bedside table. It's basic but secure. And it's comfortable … when the

power's on ... which it isn't at the moment.