|

DILI, January 2001.

DENGUE FEVER. SOUND EXOTIC? It's not. Splitting headache, full body ache, chills, skin rash, skin sensitive to the slightest draft. It's a virus carried by a mosquito with stripey rear legs. There are no prophylactic drugs or vaccination for it, the treatment is panadol and it's endemic in East Timor.

My intense symptoms have lasted three days, easing on the fourth day helped by

three litres of interveneous saline solution, for rehydration, at the

International Red Cross Hospital emergency unit. The lingering effects are

a horrid taste in my mouth and an accompanying lack of appetite, and what has been a

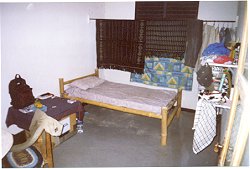

debilitating loss of energy. I can barely move beyond the veranda of my

house. The doctor said I'll feel like this for another ten days. Ten

days?!

Just the day before my collapse, I was at work and Carlito, one of the young guys I am training, came back after lunch with a boy of about eight years old. He had a deep gash on the underside of his foot just below the toes. It was beyond the bottle of Betadine and Elasterplast I carry in my day pack, so I took his hand and we slowly walked to the Comoro military hospital right next door.

The Korean sentry said that it was a military hospital and wouldn't let us through. I'd heard that this was the case but I figured I could easily sort it out when a jeep-like vehicle of Auzzie servicemen rolled up and I appealed to them. The ranking officer was adamant they would not treat the boy and that we should go to the International Red Cross Hospital in Becora. I pointed out that was eight kilometres away and that my transport was a bicycle. He still said 'no treatment' and I said to give me some materials and I'd do it.

They drove on into the compound but the driver returned five minutes later with a bottle of irrigation fluid, some antiseptic and paper stitches. He gave them to me, saying he couldn't be seen treating the boy or word would get around the neighbourhood and they would end up with queues of people wanting for treatment. I asked him what's wrong with that? It's not as though he'd be asked to treat people who didn't need it. People don't come to the doctor for amusement.

He said that when he first arrived they had treated everyone who came. After a few months some UN officials came through doing an audit of services and told them they could no longer treat civilians. He said the staff were told they would be made to pay for any bandages or medicines that could not be accounted for and that there would be no admissions that were not UN approved.

He told me it's all about money and keeping costs down. Then he told me that the Comoro military hospital has 180 health professionals that are pretty much sitting around idle waiting for uniformed people to come in sick or injured. Now, you'll have read in your newspapers about every border casualty, including serious road accidents, in East Timor. So you'll be aware it's not as though this hospital is rushed off its feet with war injured being airlifted in.

Considering there are maybe 2,000 soldiers in Dili (there are a total of about 7,800 PKF or Peace Keeping Force troops right throughout East Timor) and about 1,000 civilian UN staff, this military hospital seems like it could be more accessible and useful. I can't help contrasting this facility with the fact there are probably well over 200,000 Timorese in Dili serviced by two clinics (one with only one doctor) and the Red Cross hospital which are all swamped with patients. And swamped is no exaggeration: it took me over three hours to be seen at the Red Cross emergency unit a few days later. Having also been to Dr Dan's Bairo Pite Clinic, I estimate he would see upwards of 70 patients a day.

And there are 180 military health professionals in Comoro unable to provide their services to Timorese people.