No.195 29 October 2003

BACK

BACK

|

“ He worked with head - with heart and hand, |

|

Samuel Parnell Takes Back His Time

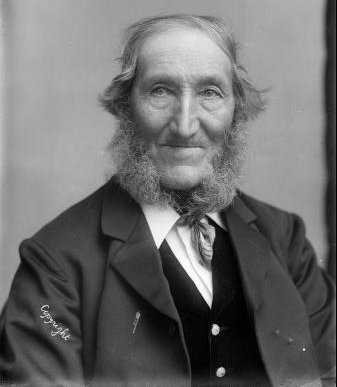

Samuel Parnell (1810-1890) who initiated the eight hour working day — Alexander Turnbull Library

In the late 1700s, American carpenters struck for the ten-hour day, challenging employers who paid flat daily wages during the long summer shifts and then switched to piecework during the shorter winter days. A movement to make this a universal standard grew throughout the nineteenth century, in response to the 70-hour weeks often worked in the new industrial enterprises.

“ Among Parnell’s fellow passengers was a shipping agent, George Hunter, who, soon after their arrival, asked Parnell to erect a store for him. “I will do my best,” replied Parnell, “but I must make this condition, Mr. Hunter, that on the job the hours shall only be eight for the day.” Hunter demurred, this was preposterous; but Parnell insisted. “There are,” he argued, “twenty-four hours per day given us; eight of these should be for work, eight for sleep, and the remaining eight for recreation and in which for men to do what little things they want for themselves. I am ready to start tomorrow morning at eight o'clock, but it must be on these terms or none at all.” “You know Mr. Parnell,” Hunter persisted, “that in London the bell rang at six o'clock, and if a man was not there ready to turn to he lost a quarter of a day.” “We’re not in London”, replied Parnell. He turned to go but the agent called him back. There were very few tradesmen in the young settlement and Hunter was forced to agree to Parnell's terms. And so, Parnell wrote later, “the first strike for eight hours a-day the world has ever seen, was settled on the spot.”• By the 1860s, the international labour movement made the eight-hour day its central focus, with marches, rallies, and related political campaigns. Wellington workers staged their first annual Labour Day celebration on 28th October 1890 and the march to Newtown Park was headed by Samuel Parnell. At the park, amid prolonged cheers, Parnell was presented with an illuminated address which paid tribute to his “noble efforts” as “the father of the eight hours movement”. As Roth records:“ Other employers tried to impose the traditional long hours, but Parnell met incoming ships, talked to the workmen and enlisted their support. A workers’ meeting in October 1840, held outside German Brown’s (later Barrett's) Hotel on Lambton Quay, is said to have resolved to work eight hours a day, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., anyone offending to be ducked into the harbour. The eight hour working day thus became established in the Wellington settlement. “I arrived here in June, 1841,” a settler told the Evening Post in 1885, “found employment on my landing, and also to my surprise was informed that eight hours was a day’s work, and it has been ever since.” The last resistance was broken, according to Parnell, when labourers who were building the road along the harbour to the Hutt Valley in 1841 downed tools because they were ordered to work longer hours. They did not resume work until the eight hour day was conceded.

“I feel happy to-day,” the old man replied, 'because the seed sown so many years ago is bearing such abundant fruit and the chord struck at Petone fifty years ago is vibrating round the world, and I hope I shall live to see eight hours a day as a day’s work universally acknowledged and become the law of every nation of the world.”

Only a few weeks later Parnell fell ill and died on 17 December 1890.

|

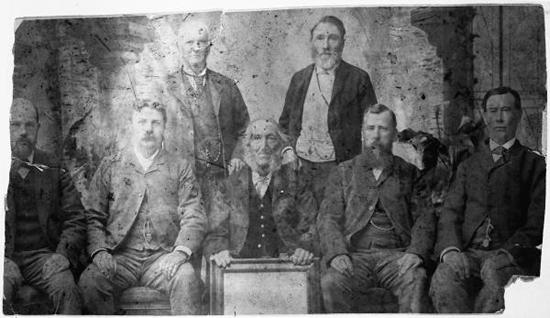

| Members of the Eight Hour Day Committee, which organised the first New Zealand Labour Day celebrations in 1890. David Patrick Fisher (left, front row) was a leading member of the Committee, and the elderly Samuel Duncan Parnell (centre, front row) was its figurehead — Alexander Turnbull Library |

• In the 1890s the Liberal Government in New Zealand passed laws to encourage the formation of unions, and Labour Day was made a public holiday in 1899. But it was not until the 1940s that the first Labour Government introduced the 8-hour day and 40-hour week as standard conditions for most workers. It was a similar case in other western countries. In 1872, a hundred thousand New York City workers, mostly in the building trades, struck and won an eight-hour day. This was followed by other workers, industry by industry, like the printers in 1906 and the steelworkers in 1923. Finally, in 1940, US President Roosevelt instituted the universal 40-hour week, with mandatory overtime when employers exceeded it.

After the Second World War, the international debate over the pace and speed of working life quietly died ... until the 1990s when changing work styles again brought attention to long working hours and the balance of our work and lifestyles.

Sources – “Parnell, Samuel Duncan 1810-1890 Carpenter, farmer, labour reformer” by Herbert Roth; “Labour Day: A History” www.nzhistory.net.nz/Gallery/Labour/index.html; “Time to Act” by Paul Loeb 1 October 2003 — Alternet

TOP TOP

|