|

A Rifkin Reader

A Rifkin Reader

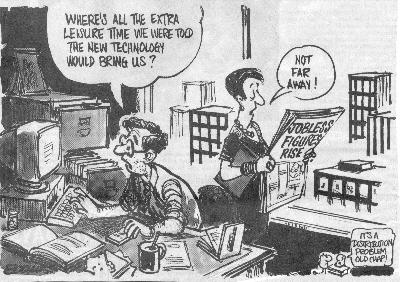

Our corporate leaders, economists, and politicians tell us that the rising unemployment figures represent only short-term "adjustments" that will be taken care of as the global economy advances into the Information Age. But millions of working people remain skeptical. In the United States alone, corporations are eliminating more than 2 million jobs annually. Although some new jobs are being created in the economy, they are for the most part in the low-paying sectors, and many are only temp jobs or part-time positions.

The global economy is undergoing a fundamental transformation in the nature of work brought on by the new technologies of the Information Age revolution. These profound technological and economic changes will force every country to rethink long-held assumptions about the nature of politics and citizenship.

|

-- Jeremy Rifkin |

Sophisticated computers, robots, telecommunications, and other Information Age technologies are replacing human beings in nearly every sector. Factory workers, secretaries, receptionists, clerical workers, salesclerks, bank tellers, telephone operators, librarians, wholesalers, and middle managers are just a few of the many occupations destined for virtual extinction.

Automated technologies have been reducing the need for human labor in every manufacturing category. Within ten years, less than 12% of the U.S. work force will be on the factory floor, and by the year 2020, less than 2% of the entire global work force will still be engaged in factory work. Over the next quarter-century we will see the virtual elimination of the blue-collar, mass assembly-line worker from the production process.

For most of the 1980s it was fashionable to blame foreign competition and cheap labor markets abroad for the loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States. In some industries, especially the garment trade and electronics, that has been the case. Recently, however, economists have begun to revise their views.

Paul Krugman of Stanford and Robert Lawrence of Harvard suggest, on the basis of extensive data, that "the concern, widely voiced during the 1950s and 1960s, that industrial workers would lose their jobs because of automation, is closer to the truth than the current preoccupation with a presumed loss of manufacturing jobs because of foreign competition...."

|

-- Jeremy Rifkin |

Acknowledging that both the manufacturing and service sectors are quickly re-engineering their infrastructures and automating their production processes, many mainstream economists and politicians have pinned their hopes on new job opportunities along the information superhighway and in cyberspace. Although the "knowledge sector" will create some new jobs, they will be too few to absorb the millions of workers displaced by the new technologies.

Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich, for example, talks incessantly of the need for more highly skilled technicians, computer programmers, engineers, and professional workers. While Secretary, he barnstormed the country urging workers to retrain, retool, and reinvent themselves in time to gain a coveted place on the high-tech express. But he ought to know better. Even if the entire workforce could be retrained for very skilled, high-tech jobswhich, of course, it can'tthere will never be enough positions in the elite knowledge sector to absorb the millions let go as automation penetrates into every aspect of the production process.

Laura D'Andrea Tyson, who headed the National Economic Council, argues that the Information Age will bring a plethora of new technologies and products that we can't as yet even anticipate, and therefore it will create many new kinds of jobs. Tyson notes that when the automobile replaced the horse and buggy, some people lost their jobs in the buggy trade but many more found work on the assembly line. Tyson believes that the same operating rules will govern the information era.

Her argument is compelling. Still, I can't help but think that she may be wrong. Even if thousands of new products come along, they are likely to be manufactured in near-workerless factories and marketed by near-virtual companies requiring ever-smaller, more highly skilled workforces.

It is naive to believe that large numbers of unskilled and skilled blue-collar workers who lose their livelihoods will be retrained to assume the new jobs that are being created. The new professionals-the so-called symbolic analysts or knowledge workers-come from the fields of science, engineering, management, consulting, teaching, marketing, media, and entertainment. While their number will continue to grow, it will remain small compared to the number of workers displaced by the new generation of "thinking machines."

Peter Drucker says quite bluntly that "the disappearance of labor as a key factor of production" is going to emerge as the critical "unfinished business of capitalist society ..."

It's not as if this is a revelation. For years futurists such as Alvin Toffler and John Naisbitt have lectured the rest of us that the end of the industrial age also means the end of "mass production" and "mass labor." What they never mention is what "the masses" should do after they become redundant ...

With near-workerless factories and virtual companies already looming on the horizon, every nation will have to grapple with the question of what to do with the millions of people whose labor is needed less, or not at all, in an ever-more-automated global economy. While mainstream politicians have embraced the Information Age, extolling the virtues of cyberspace and virtual reality, they have, for the most part, refused to address the question of how to insure that the gains of the high-tech global economy will be shared.

Up to now, those productivity gains have been used primarily to enhance corporate profits, to the exclusive benefit of stockholders, top corporate managers and the emerging elite of high-tech knowledge workers. If that trend continues, the widening gap between the haves and the have-nots is likely to lead to social unrest and more crime and violence.

The antidote to the politics of paranoia and hate is an open and sober discussion about the underlying technological and economic forces that are leading to increased productivity on the one hand and a diminishing need for mass labor on the other. That discussion needs to be accompanied by a bold new social vision that can speak directly to the challenges facing us. In short, we need to begin thinking seriously about what a radically different society might look like in an ever more automated global economy.

|

-- Jeremy Rifkin |

The new labor-saving technologies of the Information Age should be used to free us for greater leisure, not less pay and growing underemployment. Of course, employers argue that shortening the workweek and sharing the productivity gains with workers will be too costly and will threaten their ability to compete both domestically and abroad. That need not be so. Companies like Hewlett-Packard in France and BMW in Germany have reduced their workweek from 37 to 31 hours, while continuing to pay workers at the 37-hour rate. In return, the workers have agreed to work in shifts. The companies reasoned that if they could keep the new high-tech plants operating on a 24-hour basis, they could double or triple productivity and thus afford to pay workers more for working less time.

In France, government officials are considering offering to rescind payroll taxes for the employer if management voluntarily reduces the workweek. While the government will lose tax revenue, economists argue that it will make up the difference in other ways. With a reduced workweek, more people will be working and fewer will be on welfare. And the new workers will buy goods and pay taxes, all of which will benefit employers, the economy and the government.

Governments ought to consider extending tax credits to any company willing to do three things: voluntarily reduce its workweek; implement a profit-sharing plan so that its employees will benefit directly from the productivity gains; and agree to a formula by which compensation to top management and shareholder dividends are not disproportionate to the benefits distributed to the rest of the company's work force. With such an incentive, employers would be more inclined to make the transition, especially if it gave them a marked advantage over their competitors.

The second Achilles heel for employers in the emerging Information Age, and one rarely talked about, is the effect on capital accumulation when vast numbers of employees are reduced to contingent or temporary work and part-time assignments, or let go altogether, so that employers can avoid paying out benefits, especially pension-fund benefits.

As it turns out, pension funds, now worth more than $5 trillion in the United States alone, have served as a forced savings pool that has financed capital investments for more than 40 years. In 1992, pension funds accounted for 74% of net individual savings, more than one-third of all corporate equities and nearly 40% of all corporate bonds. Pension assets exceed the assets of commercial banks and make up nearly one-third of the total financial assets of the U.S. economy. In 1993, pension funds made new investments of between $1 trillion and $1.5 trillion. If companies continue to marginalize their work forces and let large numbers of employees go, the capitalist system will slowly collapse on itself as it is drained of the pension funds necessary for new capital investments.

A steady loss of consumer purchasing power and a decline in workers' pension-fund capital are likely to have a far more significant impact on the long-term health of the economy than all of the much-ballyhooed concern over the national debt and budget deficits. Of course, even an "enlightened" management is unlikely to heed the warning signals without pressure being brought to bear from both inside and outside the companies. The 30-hour workweek ought to become a rallying cry for millions of U.S. workers. Shorter workweeks and better pay and benefits were the benchmarks for measuring the success of the Industrial Age in the past century. We should demand no less of the Information Age in the coming century.

|

|

While politicians traditionally divide the economy into a spectrum running from the marketplace on one side to the government on the other, it is more accurate to think of society as a three-legged stool made up of the market sector, the government sector and the civil sector. The first leg creates market capital, the second leg creates public capital and the third leg creates social capital. Of the three legs, the oldest and most important, but least acknowledged, is the civil sector.

For more than 200 years, this sector has helped community. Our schools and colleges, hospitals, social-service organizations, fraternal orders, women's clubs, youth organizations, civil rights groups, social justice organizations, conservation and environmental protection groups, animal welfare organizations, theaters, orchestras, art galleries, libraries, museums, civic associations, community development organizations, volunteer fire departments and civilian security patrols are all part of the Third Sector.

There are currently more than 1.4 million nonprofit organizations in the United States, with total combined assets of more than $500 billion. Nonprofit activities run the gamut from social services to health care, education and research, the arts, religion and advocacy. The expenditures of America's nonprofit organizations exceed the gross domestic product of all but seven nations in the world. The civil society already contributes more than 6% of America's GDP, and is responsible for 10.5% of total employment. More people are employed in Third Sector organizations than work in the construction, electronics, transportation or textile and apparel industries.

The opportunity now exists to create millions of new jobs in the civil society. But freeing up the labor and talent of men and women no longer needed in the market and government sectors for the creation of social capital in neighborhoods and communities will cost money. The logical source for this money is the new Information Age economy; we should tax a percentage of the wealth generated by the new high-tech marketplace and redirect it into the creation of jobs in the nonprofit sector and the rebuilding of the social commons. This new agenda represents a powerful countervailing force to the new global marketplace.

In the old scheme of things, finding the proper balance between the market and government dominated political discussion. In the new scheme, finding a balance among the market, government and civil sector becomes paramount. Since the civil society relies on both the market and government for its survival and well-being, its future will depend, in large part, on the creation of a new social force that can make demands on both the market and government sectors to pump some of the vast financial gains of the new Information Age economy into the creation of social capital.

Several union leaders confided to me off the record that the labor movement is in survival mode and trying desperately to prevent a rollback of legislation governing basic rights to organize. Union leaders cannot conceive that they may have to rethink their mission in order to accommodate a fundamental change in the nature of work. But the unions' continued reluctance to grapple with a technology revolution that might eliminate mass labor could spell their own elimination from American life over the next three or four decades.

Organized labor's hopes also rest, in part, on the emergence of the civil society as a new social force. Unions are finding it more and more difficult to recruit workers in the new economy. Organizing at the point of production becomes difficult, and often impossible, when dealing with temporary, leased, contingent and part-time workers and the growing number of telecommuters. At the same time, the strike is becoming increasingly irrelevant in an age of automated production processes. Joining with Third Sector, service, fraternal, civic and advocacy organizations to exert a collective "geographic" pressure on management to share some of the gains of the Information Age with workers and local communities may be labor's best hope for success in the new era.

In addition to holding down a 40-hour job, working women often manage the household as well. Significantly, nearly 44 percent of all employed women say they would prefer more time with their family to more money.

This is one reason many progressive labor leaders believe the rebirth of the American labor movement hinges on organizing women workers. The call for a 30-hour workweek is a powerful rallying cry that could unite trade unions, women's groups, parenting organizations, churches, and synagogues.

The women's movement, trapped in struggles over abortion, discriminatory employment practices, and sexual harassment, has also failed to grasp the enormous opportunity brought on by the Information Age. Betty Friedan, the venerable founder of the modern women's movement and someone always a step or two ahead of the crowd, is convinced that the reduction of work hours offers a way to revitalize the women's movement, and take women's interests to the center of public policy discourse.

Even with more women working in the marketplace and more men at home and in the community, women are still likely to remain the primary advocates of social capital because of their long-standing relationship to the Third Sector.

Women have been the mainstay of the civil society for more than 200 years, volunteering their time to create the social capital of the country. Their contribution has gone largely unnoticed, in part because the political importance of social capital has gone largely unheralded. By politicizing the social commons, elevating the importance of social capital and making demands on the new Information Age economy to pump some of the gains into the civil society, women could help create a new third force in American politics over the next decade.

Many executives have close friends who have been re-engineered out of a job replaced by the new technologies of the Information Age. Others have had to take part in the painful process of letting employees go in order to optimize the bottom line. Some tell me they worry whether their own children will be able to find a job when they enter the high-tech labor market in a few years.

To be sure, I hear moans and groans from some corporate executives when I zero in on possible solutions although there are also more than a few nods of agreement. But still, they are willingeven eagerto talk about these critical questions. They are hungry for engagementthe kind that has been absent in the public policy arena.

Until now, politicians and economists have steadfastly refused to entertain a discussion of how we prepare for a new economic era characterized by the diminishing need for mass human labor. Until we have that conversation, the fear, anger, and frustration of millions of people are going to grow in intensity and become manifest through increasingly hostile and extreme social and political venues.

|

|

If the answer is yes, then some form of compensation will have to be made to those whose labor is no longer needed in the new high-tech, automated world of the 21st century. Tying compensation to service in the community would aid the growth and development of the social economy and strengthen neighborhoods across the country.

By shortening the workweek to 30 hours, providing an income voucher for the permanently unemployed in return for retraining and service in the Third Sector, and extending a tax credit for volunteering time to neighborhood nonprofit organizations, we can begin to address some of the many structural issues facing a society in transition to a high-tech, automated future.

Up to now, the world has been so preoccupied with the workings of the market economy that the notion of focusing greater attention on the social economy has been virtually ignored by the public and by those who make public policy. This needs to change as we enter a new age of global markets and automated production. The road to a near-workerless economy is within sight ... whether it leads to a safe haven or a terrible abyss will depend on how well civilization prepares for what is to come. The end of work could signal the death of civilization -- or the beginning of a great social transformation. The future lies in our hands.