- Full employment is the hoariest phrase in our lexicon, the true mark of a Keynesian relic. Full employment was an objective well suited to a world of unionised industrial workers, a time when fewer women worked, when there were no migrants to speak of and little competition from Third World manufactures.

Today is very different: it is full of people who work, of overworked people, of people who work desperately, all the time, in bad conditions, at the expense of their children and their social and cultural and political lives, and for whom work provides little relief from the desperation of their position. Full employment at high wages appears an impossibly remote objective to most people under these conditions, because it would mean not merely "finding a job," but finding a job radically different from those known actually to exist. For this reason, full employment has largely lost its value as a political objective.

- The Left should stop recycling Keynesian employment policies, New Deal public works and welfare programs and the Civil Rights movements. As social forces these are spent, in some cases corrupted, and as economic programs they have been outflanked. We have been losing in part because we are viewed, rightly, as the guardians of "old ideas." As such, we have lost our moral standing, our voice.

Our critique no longer penetrates very far, nor seems terribly relevant. We have said little about the inequality crisis, and what we have said generally focuses on the very rich, the truly poor, and the unemployed. We are mobilised to the worthy defence of food and housing programs, but we have had little to offer the employed worker. For these reasons, we have been bypassed on the right by the neo-liberal advocates of "education, training infrastructure and R&D," alongside "welfare reform," migration "reform" and get-tough-on-crime.

- The global economy is a fact. Globalised business has the technological and competitive edge and won't give it up. Nations which export jet aircraft cannot take the national or protectionist view. The national position has been outflanked, and the day of autarchy (if it ever existed) will not come again.

"Global unionism" intoned a California AFL-CIO leader recently, "is the only answer to global capitalism." I think this is correct. Global Keynesianism, one might very well add, is the only answer to global monetarism.

- But how to put Global Keynesianism into practice in the real world?

We must confront the global inequality crisis. For this, we must, in the final analysis, raise real wages in the countries with which our workers compete, expand their markets for our goods, and reduce their pressure on our wage structure. You cannot have this without free trade unions in those countries.

You cannot have free trade unions in the long run without democracy (nor democracy without the freedom to form unions). You cannot have democracy without human rights. And therefore, our economic agenda should really begin a long way from economic policy itself, with the campaign for human rights, democracy, and free unionism around the world.

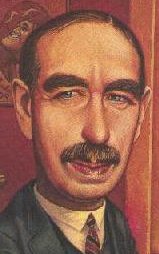

- John Maynard Keynes the economist was, above all, an optimist. And if we consider the objective global situation without succumbing to the dismal gloom of current U.S. politics, we must concede that the grounds for optimism are exceedingly strong.

First, with the arms race at an end, we could sharply reduce the military budget. Second, we have the opportunity to greatly expand our trade with 40 per cent of humanity with whom, because of the Cold War, trade was previously seriously limited. Third, and perhaps most important, there has been a burst of new technologies that are extraordinarily cheap.

The information technologies do not require enormous amounts of capital (their prices have been falling at 15 per cent per year for several decades), and have greatly increased our reach and efficiency, improving everyone's living standards. Transportation, materials science and many manufacturing processes are also all improving rapidly. Indeed, the extraordinary cheapness of new productive technology is perhaps the single defining feature of our age.

- The term "global Keynesianism" means only some system - a mechanism that has not yet been worked out - for managing interdependence to achieve high economic growth and employment, a common rising standard of living, and a minimum of financial instabilities attendant to higher growth.

The great economic powers -- the United States, Germany, Japan -- must stop thinking in purely national terms and start thinking of the larger community of which they are a part. They must understand that the growth of income in the countries to which they sell eventually determines the growth of income in their own countries.

We have not faced the responsibilities of interdependence since the end of the earlier Keynesian period and breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s, perhaps not since promulgation of the Marshall Plan. We have abandoned governmental power to market forces, particularly to the global capital markets and the large financial institutions that play in them. However, market forces cannot replace governments in the functions of governance -- neither within national boundaries nor in relations between nations.

- We can harbour no illusions about the difficulty of rebuilding a multinational structure dedicated to growth and employment, and of controlling the powerful private forces whose interests would be threatened by our doing so. However, this very difficulty is in one way a virtue. We have suffered because of the short shelf life of the various economic theories put forth over the last 25 years. We try one thing, if it fails to work in a few years, we throw it out.

But if our current difficulties force us to think our problem through to the end and to adopt a set of ideas that contain a vision to which the public can respond -- a vision that holds out neither pointless sacrifice nor immediate gratification but the serious possibility of positive results in a medium and long terms-- we may be able to free ourselves of the cycle of short-lived economic theories, with their false promises and perceived failures.

- About James K Gailbraith

Sources --

- "A Global Living Wage"

gopher://csf.Colorado.EDU:70/00/econ/authors/Galbraith.Jamie/

Global-Living-Wage-PQ.Fall.95

- "Global Keynesianism in the Wings"

gopher://csf.Colorado.EDU:70/00/econ/authors/Galbraith.Jamie/

Global-Keynesianism-in-Wings.Oct.95

- Some Tributes to a Forgotten Revolution

- About John Maynard Keynes 1883 -- 1946

- Robert Reich on John Maynard Keynes

- James K Galbraith on Global Keynes

- Some Tributes to a Forgotten Revolution

James K. Galbraith

on Global Keynesianism

an essential summaryedited by the Jobs Letter

James K. Galbraith is Professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs and Department of Government, The University of Texas at Austin, and co-author of Macroeconomics, a textbook from Houghton-Mifflin.

They retreated from any the idea that the government's economic policies should aim at achieving full employment, adopting the view that efforts to reduce unemployment were not only futile but also likely to be inflationary -- that you would get only a temporary decrease of unemployment in return for a permanent and intractable increase of inflation. This put macro-economic policy, the manipulation of budget deficits and interest rates to achieve grand goals of employment and growth, on the sidelines. Economic policy moved from the macro to the micro, from the demand side to the supply side, from a focus on accounting aggregates to focus on individual incentives.

James K. Galbraith in "A Global Living Wage" -- Political Quarterly Fall and "Global Keynesianism in the Wings" -- World Policy Journal Fall 1995

Original Articles are available on the internet :

The decline of Keynesianism that began a quarter-century ago was an ambiguous event, since the Keynesians, helped along by the economic effects of the Vietnam War, had reduced unemployment to below 4% in 1969, at an inflation cost that was both predicted and quite moderate by later standards. But during the 1970s, economists came to see economic problems that might have passed into history as mistakes of policy and external shocks, as, instead, the result of fundamental errors of theory.

The decline of Keynesianism that began a quarter-century ago was an ambiguous event, since the Keynesians, helped along by the economic effects of the Vietnam War, had reduced unemployment to below 4% in 1969, at an inflation cost that was both predicted and quite moderate by later standards. But during the 1970s, economists came to see economic problems that might have passed into history as mistakes of policy and external shocks, as, instead, the result of fundamental errors of theory.

Top of Page

The Jobs Letter Home Page

Hotlinks |

Stats |

Subscribe |

Index |

Search

The Website Home Page

jobs.research@jobsletter.org.nz

The Jobs Research Trust -- a not-for-profit Charitable Trust

constituted in 1994

We publish The Jobs Letter