She has travelled the world bearing a sign: "American Willing to Listen", made peace with a manufacturer of napalm and got the botanic gardens replanted in war-torn Dubrovnik. GOOD WILL HUNTING

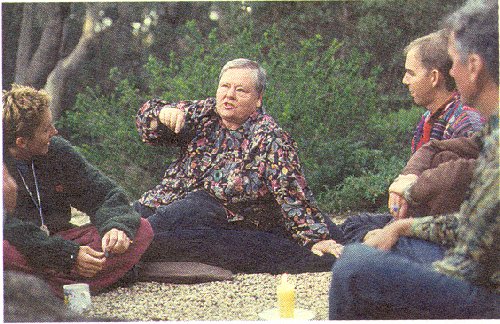

Fran Peavey in Australia 1998

David Leser meets activist Fran Peavey, the kindly guru of heart politics.

-- from The Melbourne Age "Good Weekend" Edition 30 May 1998

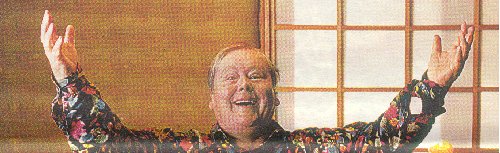

WHEN FRAN PEAVEY laughs, her flesh wobbles. Her chest heaves, her ears bob and her jowls roll and toss. Hers is the chortle of a woman who has found her stride in middle age; who has travelled psychological light years from her home in Idaho and the crippling sense of herself as the fat little girl who should be hiding in the wings.Today, Fran Peavey is delicious, living proof that agents for social change come in all shapes and sizes and, more often than not, in shapes and sizes that defy the hoary, media-driven stereotypes of how a person should best present to the world.

"You will notice that many social-change people are a little different," Peavey says. "They have not invested themselves in the status quo. They have given up, in one way or another, passing for okay. They've never been okay.

"Social-change people as a whole are often marginalised, physically, emotionally or intellectually. As far as I'm concerned, I don't have any investment in the way things are because I don't see my people [as part of the status quol. I don't see any large women doing a lot of great stuff, so there's nothing to keep me from doing it."

Fran Peavey has been doing a lot of great stuff for a long time. Since the end of the Vietnam War, social change has been her life's goal. She has worked with elderly Asians to prevent their eviction from a residential hotel in San Francisco; forged an alliance with Thai prostitutes to thwart their removal from a Bangkok neighbourhood; campaigned in India to save the Ganges River from being destroyed by pollution; helped feed the homeless of Osaka and performed comedy skits around the world to illuminate the absurdity of living under the threat of nuclear annihilation.

For more than half her life, in fact, Peavey has been at the barricades, challenging the status quo, trying to build a new culture of peaceful co-operation and social justice, and if that all reeks of good old-fashioned, 1960s-style agitation, then so be it. Peavey is unapologetic about the fact that her politics have been shaped by the American black civil rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War protests and the Cold War.

She has grown up believing that, by protesting, marching, demonstrating, writing letters, singing songs, forming committees, creating communities of kindred spirits, you can actually change the world, even though, in her case, it has involved much personal risk and injury.

For her troubles, Peavey has had her tailbone broken, been beaten around the head, and been intimidated and threatened more times than she cares to recall. She has also been jailed at least 16 times. She simply keeps coming back for more.

But, that said, it would be wrong to see her as simply a throwback to the days of Haight-Ashbury and Kent State University. It would be wrong to see her work as simply an exercise in naivety or nostalgia, although her rhetoric is spiked with both.

It's fairer to say that this 57-year-old American maverick reminds us that there are things we can all do to bring about necessary change, big and small. There are issues that can be taken up, there are depths of courage that can be plumbed, support and respect that can be affirmed, links that can be established in the face of the most seemingly insurmountable obstacles. In other words, there is change that can he wrought at every level - psychological, spiritual, political, communal - with the right will and intent.

Indeed, Fran Peavey reminds us that ordinary people can make a difference.

The first time we met was in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, where a group of about 80 people had come for a so-called "heart politics" gathering. Heart Politics is the title of Peavey's first book and the name given to a loose coalition that has sprung up in Australia, New Zealand and the United States for the purposes of bringing about social, political, cultural, environmental and economic change through "compassion", through a tuning of the heart to the world's affairs.

It is political to the extent that it challenges the status quo and affirms the possibility of a more just and humane future. It emphasises the links between personal and political action. It stresses the need to respect those we oppose, as much as those we support. It eschews simplistic solutions, but endorses the idea that the common good can best be realised by people operating from their hearts as well as their heads.

Briefly in Australia on a speaking tour, Peavey was sitting like some Falstaffian figure surrounded by men and women from the coalface of activism, people involved in women's health, migrant and refugee work, sustainable agriculture, forest protection, Aboriginal reconciliation, parenting... They had gathered for a weekend to remind themselves that their work did make a difference, that they could find support in each other and that the words of a woman whose self-proclaimed "fat little feet" have taken her across the globe in the name of social change were well worth listening to.

"We have to find and give each other stories that will make us feel that things are not impossible," she told the gathering. "We have to make changes without losing our humanity. I am trying hard to learn to do that. I am trying to learn to build bridges to people who are different to me." Peavey then proceeded to regale her audience with stories that exemplified the meaning and spirit of heart politics. She talked about a meeting she'd had during the Vietnam War with the head of a napalm factory. The meeting had been arranged days after an explosion at the factory had caused napalm to fall on surrounding houses.

Peavey was trying, with other peace activists, to get the factory shut down. She researched every aspect of the company's activities and investigated the background of the company president. She wanted a profile on her "true enemy" before she looked him in the eyes. The last thing she expected to find was a "human being".

"We found out that he had a wife and two children, that he attended the Presbyterian church and belonged to a certain golf club," she said. "And then we started to see him as someone who was loved by his family and had a place in the community." When she and her colleagues eventually met the president, he offered them food and peppered them with questions about their views on the war. He then asked: "How does your work feed your spiritual life?" Peavey was amazed. A manufacturer of napalm, an enemy of the peace movement, inquiring about spirituality? Their talk dragged on into the afternoon, with Peavey urging him to desist from "the business of burning people".

A few months later when a new contract was drawn up for the production of napalm, the factory president declined to make a bid. He'd decided to put his factory to another use. To this day, Peavey is not certain whether their discussion prompted his change of heart, only that it was a "miracle" they'd been able to discover each other's humanity.

"It's easier to be prejudiced against people you've never met," Peavey has written in Heart Politics. "Fear and hatred can thrive in the abstract. But most of us, if given a protected situation and a personal connection to the people we thought we feared or hated, will come through as compassionate human beings." And this is why Peavey calls her organisation Crabgrass. On the surface, each blade of crabgrass appears to be an independent plant yet, on closer inspection, is connected to the other blade of grass through a common root stem.

It follows, therefore, that taking sides runs counter to the principles of her organisation and heart politics in general. In the final analysis, all protagonists, no matter who they are - black American and white, Hutu and Tutsi, pastoralist and Aborigine, Serb and Croat - are connected by their common humanity; by the slim thread of possibility that an ally can be made from an adversary.

The old Yugoslavia is a case in point. Peavey has seen extraordinary acts of courage, of forgiveness, in places like Sarajevo, a city she describes as having suffered "360 degrees of destruction". She has seen Serbs cared for by Bosnian Muslims, despite the fact that it was Serb forces who'd been largely responsible for the city's nightmare. She has seen people putting their lives on the line for their so-called enemies, crossing ethnic and ideological borders to build invisible bridges.

Before the Balkans war, Peavey had been fascinated by "social insanity", by what happened when a community or an entire country went crazy. She had studied the Holocaust, and the Jewish declaration "Never Again" had long since burnt itself into her consciousness. When the Yugoslav genocide began unfolding in the early 1990s, she wanted to help. She also wanted to learn whether the signs of the approaching apocalypse had been telegraphed and, if so, what those signs might have been.

Peavey appreciated there was little she could do from her home in San Francisco, so she decided to go to Yugoslavia, link up with anti-war groups and find out what their needs were on the ground. What she found in Dubrovnik was that this one-time jewel of an Adriatic city had been all but destroyed by Serb shelling. The botanic gardens, for instance, were in ruins.

Peavey returned to America and, via Crabgrass's mailing system, recruited a volunteer gardener for the ravaged gardens of Dubrovnik. This was heart politics at work. "That gardener pledged to come back [to the US] and tell people what she'd learnt about ethnic cleansing," Peavey explains. "Because the things that we learn in Yugoslavia help us understand, first of all, how it feels and, second of all, what the tremendous costs of nationalism and hatred are."

So appalled was she by the Yugoslav tragedy that, on her return to America, she also wrote to 67 of her friends asking each to put together a package of lotions, shampoos, scarves and perfume for the women who'd suffered the loss of loved ones, ~been raped during the war, or both. A friend of hers in Australia sent a similar letter to another 20 Australians. Together they hoped for 200 to 300 packages. Instead, they received 8,000.

"People said to us, 'I've been aching to do so something.' They just didn't know what to do. It was like a dam holding back the caring and my little old letter gave them something to do."

On returning to Yugoslavia, Peavey handed out these packages to the women. She travelled from refugee camp to refugee camp listening to stories of abject horror and, in the listening, attempted to show that there were those on the outside who cared. "You know, when I'm listening [to these stories]," Peavey says, "I just let the tears flow. The tears just seem to fall down my little fat cheeks and it's just sorrow. It's just sorrow.

"And we have to be alive to that in our world in order to work ... but also to face our own helplessness because we have to face the fact that there's no single thing we can do to make anything right. There are. many things that must be done and we can only do one little, tiny piece."

FRAN PEAVEY is from Twin Falls, Idaho. According to the family plan, she was supposed to marry an Idahoan businessman, become a teacher and bear an appropriate number of Idahoan children. At some stage in her growing up, the plan fell to pieces.

Her father was a successful insurance salesman and staunch member of the Republican Party. Her mother, a former teacher, stayed home to raise her five children. Peavey admits it was difficult not being the "svelte, feminine daughter" her mother had always craved.

"Even now, 1 look at pictures of myself as a highschool kid and I don't look fat; to me, you would not look at that person and say 'fat' ... but my parents did. They were always harassing me about dieting ... that I should never step out front because I was so large.

"I've since become a professional comedian [but before that] occasionally in school plays, 1 would be out front and it embarrassed my mother. She wanted a beautiful daughter and she didn't get a physically beautiful daughter." Peavey is grateful to her mother, however, for instilling a basic sense of right and wrong. Her mother explained how, say, Mexican farm workers were being treated in the hinterland around Twin Falls. She encouraged her children to believe in participatory democracy.

As for beliefs in feminism, they were largely the legacy of her grandmother. "Grams" Peavey was one of the first women graduate students at Stanford University. She was a voracious reader of books and magazines like The New Yorker and Atlantic Monthly. She once told her grand-daughter that a woman could best ward off unwanted advances from men by carrying an Atlantic Monthly with her and thus appearing intellectual.

Grams Peavey was also the first to expose her grand-daughter to pacifist ideas; to awaken her to the idea that most, if not all, wars were economic in their origins and that "peace at any price" should, indeed, be the goal. Needless to say, Fran Peavey took that message to heart.

Peavey is probably the only American to travel the world bearing a sign saying "American Willing to Listen". After years of political activism - civil rights demonstrations, workshops around the US, doctoral work in "innovation theory and technological forecasting" - she wanted to know what the rest of the world thought about some of the more pressing issues of our time.

She sold her house, paid off her debts and bought an around-the-world ticket. Her first destination was Japan. Waiting for a train in Osaka, she pulled out her large cloth sign and waited. After about 40 minutes, a man stopped to ask her what she was doing. She said she wasn't sure. He walked away shaking his head. Another 10 minutes went by and another man sat down. Peavey explained she was there to, listen to him. Eventually, in broken English, he began to share some of his concerns. He talked about the border war between North and South Korea, rampant consumerism in Japan, relations between the sexes. Afterwards, he thanked Peavey for what she was trying to do.

"My confidence grew as the process of meeting people gained momentum," Peavey says. "I met people by arrangement and at random, in their homes, schools and workplaces, as well as in cafes, train stations, universities and parks. I refined my interviewing technique, asking open-ended questions that would serve as springboards for opinions and stories questions such as 'What are the biggest problems you see affecting your country or region?' and 'How would you like things to be different in your life?' "

Twenty years, scores of countries and thousands of interviews later, she has an acute sense of social and historical currents around the world. She might not own her own house; she might have to rely for her income on the modest sums that five wealthy San Franciscan women give her each year; she might not have an Idahoan husband (in fact, she has a woman partner whom she married in a civil wedding); and she might have borne no Idahoan offspring, but she knows a thing or two about forging links with grassroots organisations and working for non-violent change.

For 16 years, Peavey has travelled regularly to the holy Indian city of Varanasi to link up with local groups in an attempt to address the horrendous levels of gastrointestinal diseases caused by parasites in the Ganges River. Thousands of children have died because of elementary neglect - no water-testing laboratory, no treatment for faecal coliform, no effective sewage treatment plants, no electric crematoria for the burning of bodies.

When she's not in India or Bosnia, she can often be found in her San Francisco apartment, advising those in the Bay. area who care to seek her out. Last year, a group of teenagers came to her, incensed by a local shopping mall's decision to prohibit skateboarding. "We hear you work with the oppressed," they said. Peavey took up their cause. They reminded her of what it meant to be young and powerless. Five months later, she finally managed to secure a parking lot that would allow skateboarding. The teenagers claimed a tremendous victory.

FRAN PEAVEY was reluctant to do this interview. She believes her best work is done on the quiet, without fanfare. She also believes that the media is wedded to presenting a world in chaos. It rarely tells stories of ordinary people doing fantastic, heroic, dignified things in the name of building communities and bringing about social change.

But she relented, mainly because of her hope that this article might encourage Australians to enter into the spirit of heart politics. 1 love this place," she says. "This is a grand country. The people here have a greatness in their ordinariness that they don't really see.

"When 1 first started coming here 10 years ago, there was very little understanding of the genocide that had happened on this land. Now there's this controversy [over Wik] and so there's a new chance for Australia to either [redress] the past or for ethnic violence to continue at a deeper level.

"I'm just holding my breath for Australia because when we're in the United States we hear such crazy things that racism is running riot in your streets, that there are people standing up saying really bizarre things, and I'm sitting over there saying, 'How can this be, my beloved Australia?' So 1 come here and I find another Australia from the one that gets in the press - which is always the case. I see a decency here that 1 learn a lot from. This Sorry Book campaign; the [Sea of] Hands [for Native Title] project, the fact that everywhere I go there is an Aboriginal person to welcome you. That never happened before.

"We are not nearly as advanced in America as you are in Australia. You are moving in such profoundly deep places in this [reconciliation] work. You are at the face of the mountain."

But what does she say to the people who are too consumed by the dramas in their own lives to go beyond them? What does she say to those too frightened of the future, too despondent about the past, too alarmed by the destruction of our environment and the fraying of the social fabric to fight that sense of hopelessness? "People will solve their problems more profoundly," she replies, "when they join with others and work on their common problems. That's actually the best way to fight depression - get active on a larger scale.

"Now, of course, the biggest criticism of heart politics is that it's 'so naive'. And it's true, there is a lot of evil and despair in the world which makes it difficult to know if we will he able to make the changes necessary for life to thrive on earth.

"We don't know, but we have to do our bit because I know, one day, I'll be lying on my bed and the Grim Reaper will come and I'll want to be able to tell myself I did the best I could.

Interview by David Leser

Published 30 May 1998